Amid an increase in global demand and concerns over key supplies, global oil prices are approaching $100 per barrel for the first time since 2014. But, with prices rising, what does this mean for the renewable energy transition, especially in Gulf countries?

After opening the year at around $78 per barrel, Brent crude prices rose sharply over the first six weeks of 2022 to surpass $94 as of February 14, the highest price in more than seven years.

Driven primarily by a lack of supply and a recent post-lockdown spike in global demand, the increase caps off a dramatic recovery of prices, which had fallen to less than $20 a barrel in April 2020.

Given the low oil price environment of the last couple of years, the recent increase has prompted discussion about the implications for investment in renewable energy, particularly for oil-exporting countries in the Gulf.

Although investment in oil and gas has fallen by about 30% since the outbreak of the pandemic, there are signs that the increased demand and rise in prices could lead to a reversal of that trend.

Carbon Tracker, a London-based climate change-focused think tank, noted last month that higher oil prices might encourage energy companies to invest in new exploration and production projects.

Indeed, on February 1 energy giant ExxonMobil announced a 45% increase in its budget for drilling and other activities this year, while a day later members of the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries and other leading oil-producing nations – an alliance known as OPEC+ – agreed to stick with their pre-planned target of increasing oil production by 400,000 barrels per day.

At the same time, there are concerns that higher oil prices could incentivise the consumption of coal, which reached an all-time high in 2021 and is on track to reach even higher levels this year, according to the International Energy Agency.

In addition to its lower price, coal use is being driven by rising energy demand – led by China and India – and insufficient levels of investment in renewables.

A boon for renewables?

Although high oil prices have the potential to incentivise new investment in oil and gas projects, renewables could ultimately benefit from the current situation.

Rather than directly challenging renewables and slowing the energy transition, many energy industry analysts believe that the current high prices – and the associated financial windfall – could lead governments and oil majors to play the long game and further increase their investments in renewable energy.

For example, in September last year French energy giant Total said it would take advantage of high oil prices to buy back $1.5bn in shares to boost investment in renewable energy, while earlier this month BP – upon announcing its highest annual profit in eight years, at $12.8bn – stated it would increase spending on low-carbon energy to 40% of total spending by 2025 and 50% by 2030.

Gulf pushing ahead with renewables

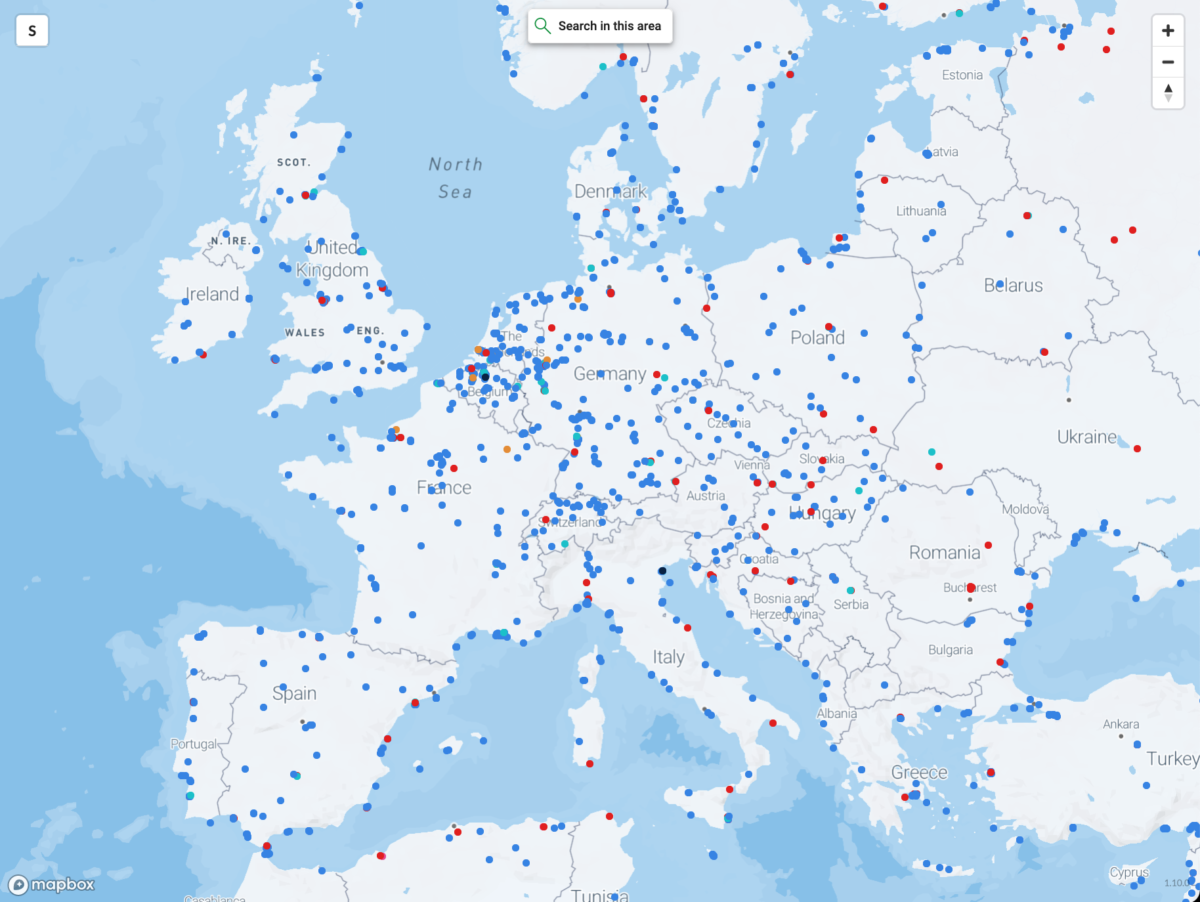

A prime example of an oil-producing region that has recently reaffirmed its commitment to renewables is the Gulf.

Indeed, many Middle Eastern countries have identified the development of renewable energy as key to their long-term economic diversification plans.

For example, Saudi Arabia aims to generate 50% of its electricity from renewables by 2030 and has set a net-zero target of 2060.

To help achieve these goals, in December the government announced that it would invest SR380bn ($101.3bn) in renewable energy production by the end of the decade, while in April last year it inaugurated the Sakaka solar power plant, the country’s first utility-scale renewables project.

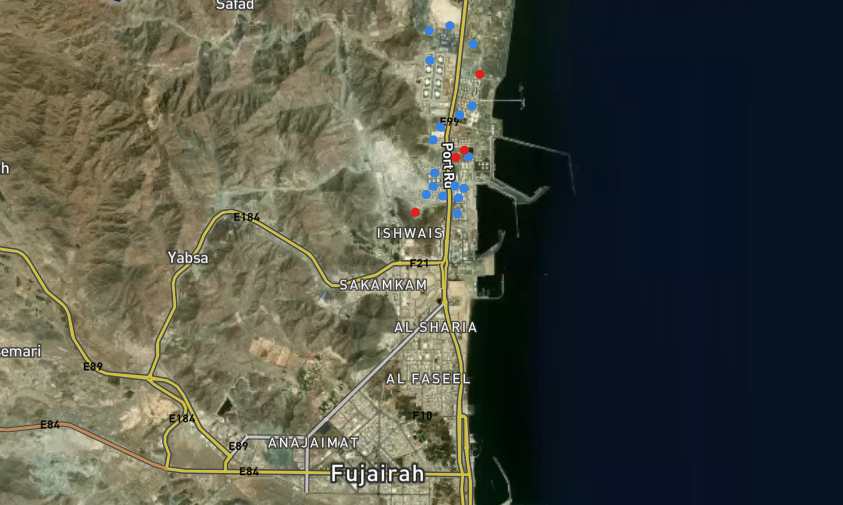

Meanwhile, in October the UAE pledged to invest Dh600bn ($163.4bn) in renewables by 2050, at which point it hopes to achieve net-zero emissions.

The announcement came just a few weeks after the inauguration of the first stage of the Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum Solar Park in Dubai. The park is expected to have a capacity of 5 GW by 2030.

Elsewhere in the region, in late January Oman inaugurated the 500-MW Ibri 2 solar field, the country’s largest utility-scale renewables project, while Qatar, one of the world’s largest exporters of natural gas, has also increased its focus on renewables.

In October last year Qatar Petroleum, the national energy company, changed its name to Qatar Energy, in order to better reflect the company’s renewables-focused strategy.

Major projects include the 800-MW Al Kharsaah Solar plant, located approximately 80 km west of the capital Doha.

Once fully completed, the project will be the country’s largest renewable energy development. It is set to be inaugurated in the first half of this year.

While there is some scepticism as to exactly how much of the financial windfall associated with high oil prices will go towards the energy transition, and whether net-zero ambitions can be achieved if funds continue to be channelled into new exploration and production projects, it is clear that renewables are playing an increasingly important role in the long-term energy plans of companies and governments alike.

OilPrice by Oxford Business Group, February 21, 2022