It is widely thought that a future low-carbon hydrogen industry will arise in industrial clusters.

The emphasis is on ports, where concentrations of basic industries, pipelines, and shipping will support large scale production and efficient supply. Plans for major industrial ports in Europe, such as Antwerp and Rotterdam, are enhanced with the possibility of offshore storage of carbon dioxide. In the US, the region that appears best equipped for widespread adoption of clean H2 is the Texas Gulf Coast centered on Houston. The Houston region’s industrial sector comprises approximately 30% of US refining capacity and more than 40% of US petrochemical capacity. Its industrial sector accounts for 40% of the state of Texas’ industrial emissions.

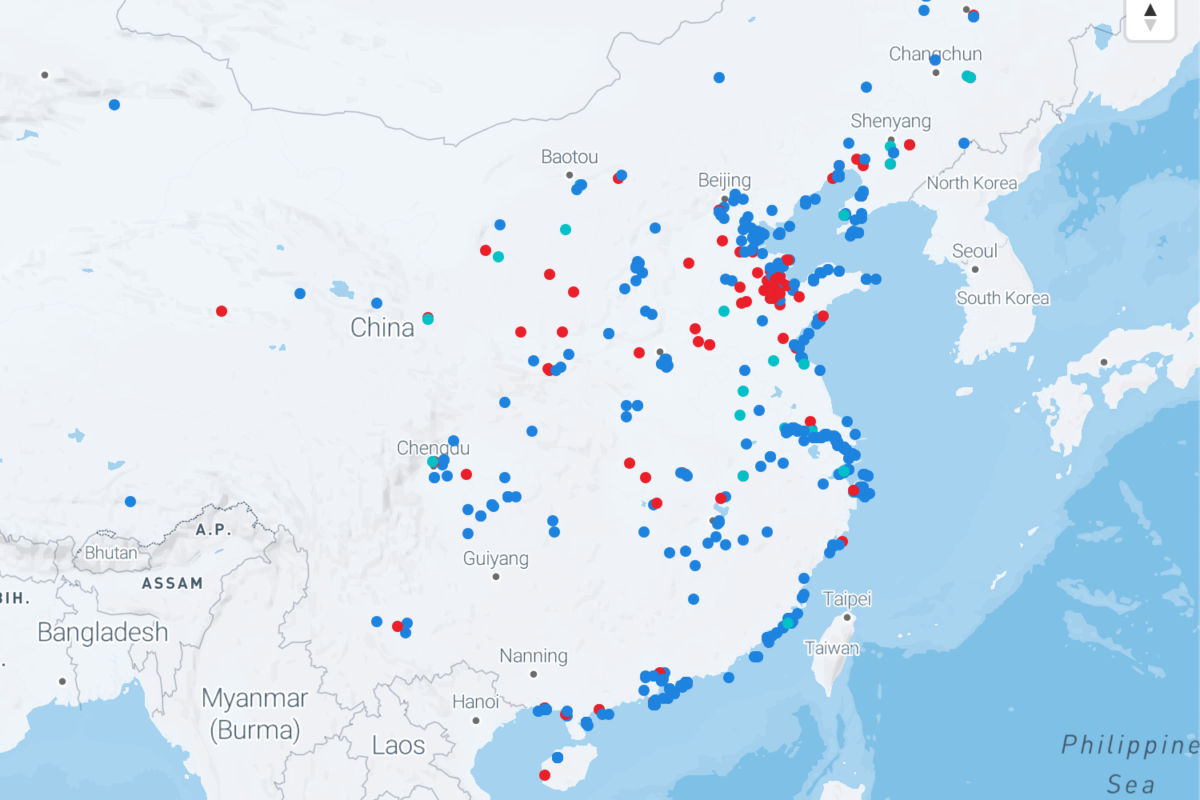

This vast industrial landscape of refining, petrochemicals, and related industries already consumes one-third of current US hydrogen production, almost all of which is produced from natural gas by the steam methane reforming (SMR) process. Nearly 50 SMR facilities, operated by major merchant producers such as Air Liquide, Air Products, and Praxair, exist along the Gulf coast. They connect to over 900 miles of dedicated hydrogen pipelines, which account for more than half of the US’s hydrogen pipelines and close to an astonishing one-third of H2 pipelines worldwide.

This large existing market for industrial hydrogen lays over a regional geology that should support storage: salt caverns for temporary storage of hydrogen gas; and undersea caverns for the perpetual storage of carbon dioxide beneath the Gulf of Mexico.

These favorable attributes have spurred serious consideration of how a ‘hydrogen hub’ might emerge. The possibility of assembling all of the pieces required for a clean H2 system, linked to local industries as well as national and global export markets, has appeared.

But all of the pieces required for a functioning system remain for now separate pieces, most of them in very early stages of development. The possibility of turning Houston’s gray hydrogen into blue or green hydrogen will depend on effective public policy being put into place.

CCS ‘Innovation Zone’

ExxonMobil Corp. is thinking seriously about a hub concept for Houston, where the company has a major corporate campus, large refinery complex, and more than 12,000 employees.

The oil major announced its intention to explore the viability of carbon capture and storage (CCS) in the Houston area last spring. Then, in September, it was joined by a working group of ten more companies that expressed interest in working together to support large-scale CCS infrastructure.

It’s an impressive list, including Calpine, Chevron, Dow, INEOS, Linde, LyondellBasell, Marathon Petroleum, NRG Energy, Phillips 66 and Valero Energy Corp. According to ExxonMobil, the 11 companies represent nearly 75% of Houston’s industrial and power generation CO2 emissions.

While no formal structure has been created, their discussions continue and the 11 companies intend to have more announcements in the first quarter of ’22.

A likely leader will be ExxonMobil Low Carbon Solutions, a subsidiary business launched in early 2021 to initially focus on CCS projects worldwide, with projects and partnerships in nearly a dozen countries. For the Gulf project, it is focusing on an effort to capture emissions from industries along the Houston Ship Channel that comes miles inland from Galveston Bay.

The company’s proposal would be the world’s largest CCS project, storing 50-100 billion tons of carbon dioxide annually by the year 2040 in old oil and gas formations beneath the sea floor of the Gulf of Mexico.

It might seem improbable that huge quantities of carbon dioxide could be carried by pipeline to reservoirs thousands of feet below the sea floor, beneath impermeable rock, but technically it’s feasible. Indeed, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) has estimated that storage capacity along the U.S. Gulf Coast is enough to hold 500 billion metric tons of CO2. It is more than 100 years of total industrial and power generation emissions in the US.

The challenge is to finance it. ExxonMobil thinks the project will require $100 billion. The company envisions something of a collective effort, with government and industry collaborating on an ‘Innovation Zone’ approach.

“We envision a ‘zone’ approach, similar to other public-private initiatives established to facilitate economic growth or tackle other broad societal challenges,” says Joe Blommaert who is president of ExxonMobil Low Carbon Solutions.

Such a collaborative effort will be no easy matter to build. ExxonMobil asserts that funding must be a mix of public and private, with public sector subsidies and incentives combined with support from across industries. Appropriate regulatory and legal frameworks must be established to enable investment.

But the lever to put it all together, ExxonMobil acknowledges, may well require some form of carbon tax. The company has stated publically that it is in favor of establishing a market price on carbon in order to drive investment in large-scale CCS.

Getting H2 going in the Texas Triangle

Another perspective on Houston’s huge hydrogen potential appears in an influential new report entitled ‘Houston Region: Becoming a Global Hydrogen Hub.’ Produced by the civic group Center for Houston’s Future, the report lays out a tentative pathway to deploying the many elements of Houston’s industrial complex to build a viable low-carbon hydrogen economy.

Nearly all of the Gulf coast’s widespread hydrogen apparatus was built for the region’s refining and petrochemical industry. To extend production into clean hydrogen and to get it into the energy system, the Hydrogen Hub report looks at the problem in a phased way, separate from the ExxonMobil project.

“To begin, we can start small, just to get hydrogen into the system and leverage that,” says Andy Steinhubl, who is Chair of the Center for Houston’s Future and a board member of GHI (Green Hydrogen International).

He explains that an initiative to activate clean H2 must occur in a sector where the cost of hydrogen can compete with existing fuels now or in the near future. The Hydrogen Hub report asserts that comparative economics strongly favor heavy trucking for an activation phase.

“Trucking is the ‘killer app,’” says Steinhubl. “It (hydrogen) competes favorably with diesel fuel on price, the infrastructure is largely in place, and the truck technology is almost there,” he adds.

He points out that the underlying technology is quickly emerging, as vehicle manufacturers such as Hyundai, Toyota and Nikola continue work on fuel cell electrified trucks that can match diesel engine torque and horsepower. They intend to supply heavy trucks to shippers who will increasingly seek to curb emissions.

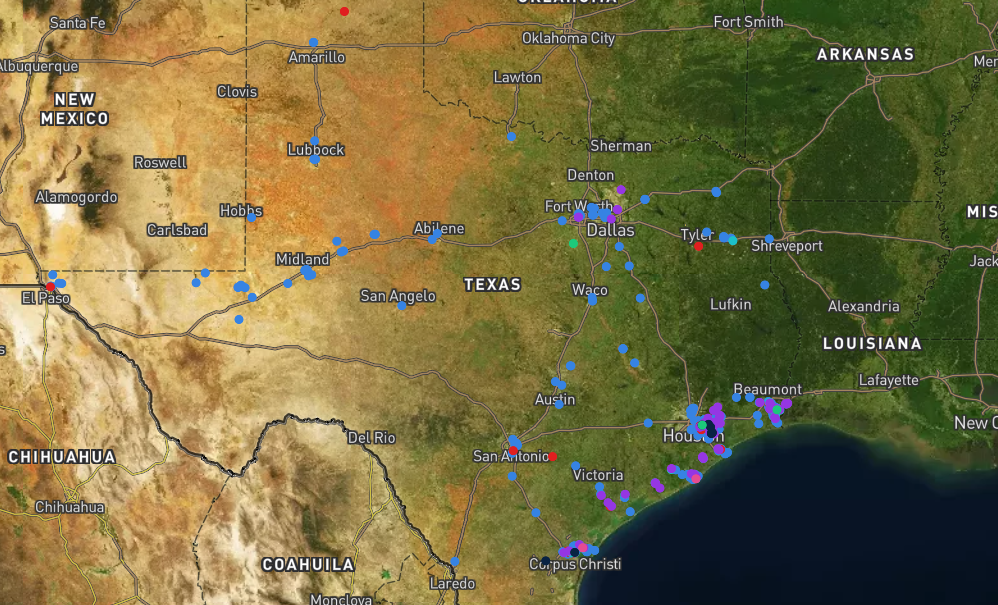

To get this early H2 market going in Texas, Steinhubl is looking at the I-45 Houston-Dallas corridor.

“We could literally start a system tomorrow,” he says, “with a refueling station in the Houston port, another in the Dallas warehouse district, and trucks making the non-stop 3.5 hour trip between them on Interstate 45.”

In fact he sees a hydrogen truck triangle becoming feasible. I-45 would be the first leg or side of the triangle. The service could add I-35 from Dallas to San Antonio, and I-10 from San Antonio to Houston. The distances are all similar and would not require the trucks to stop for fuel between them. Local service would also be feasible in the dense cluster of industries, refineries and privately-owned ports along the Houston Ship Channel.

All of this could start with pilot projects requiring modest initial investment.

“A few refueling stations, a few trucks, extend a pipeline or repurpose an H2 delivery truck and off we go,” says Steinhubl.

Still it will require significant coordination and value chain development.

“We will need to build a coalition of relevant players across the value chain – shippers, logistics companies, a hydrogen producer, a fuel station operator (possibly Shell), a truck manufacturer, a local port and government.

“We will need to identify pilot locations and scope – how many trucks, point of refueling, where fuel is coming from and arriving at, etc.,” he says. “Then, secure funding and execute.”

This nascent market would likely begin with gray hydrogen, already in abundant supply in the region, produced with inexpensive natural gas from the Permian Basin of West Texas. Indeed, the size of the Houston area’s existing H2 system is so vast that a hydrogen trucking pilot would add little additional carbon emissions.

Steinhubl is quite certain that such fuel powering fuel cell trucks could compete with diesel.

“The reason why trucking is a ‘killer app’ is there isn’t a cost of supply vs alternative fuel issue. Nor availability of supply. Just need to get downstream pieces lined up,” he says.

“On trucking ‘supply’ the infrastructure is nearly already there. And H2 trucking tech is in place. We just need to make the trucks, which requires a customer.

“So it requires creating a new chain, a whole new end to end set of interrelationships. No piece moves without the others – we need to incent them all to move together.”

Of course, in addition to deploying hydrogen in trucks, extending production into clean hydrogen will require carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS). That too will require dedicated financial support and incentives to become part of the value chain.

The Texas-based energy company Denbury Inc., which specializes in carbon capture for enhanced oil recovery, manages an extensive CO2 pipeline network east of the city of Houston. This Denbury system could play a critical role.

Global hydrogen hub

While a heavy truck pilot could be launched relatively quickly with the region’s existing hydrogen infrastructure, a broader application of clean hydrogen will require much more work. Among the oft-listed potential hydrogen markets, such industrial heat, power production, or building heating, no clear winner emerges now. The costs are still too high.

Steinhubl points out the difficulties for an industry such as steel making. The hydrogen molecule is so small that the metallurgy of current processes is not compatible; a conversion to hydrogen fuel will require redesigning the plants.

What’s needed now is more public support. DOE has earmarked $8 billion for four hydrogen hubs and Houston intends to be selected as one of these in 2022. There is also the 45Q tax credit that companies and utilities can apply for carbon capture projects, but proponents say it needs to be expanded.

There is a lack of clean fuels incentives in Texas, where proponents of large-scale hydrogen projects can only hope for the kind of support seen in the EU and the UK, with their carbon taxes and direct subsidies, or in California with its Low-Carbon Fuel Standard.

Nevertheless, Texas enjoys important advantages that will help. An important example for a trucking pilot is the Port of Los Angeles, which now has 10 hydrogen fuel cell trucks deployed into service, with three refueling stations to be open in ’22. Such a pilot project would likely require fewer incentives to get up and running in Houston, given its hydrogen advantages and dense patterns of heavy trucking.

A fairly rapid start-up of green hydrogen pilot projects may also be feasible. Here Texas has at least one unique advantage, given the significant power consumption requirements for electrolysis. Texas is the largest wind power producing state in the US and has a rapidly growing solar fleet. The state’s power market enjoys many hours of low-priced excess power due to its generation mix heavy in wind power.

This advantage for green H2 should grow as renewable power penetration increases in the state, while electrolysis costs and production efficiencies improve. For example, an early market opportunity for green H2 could be found in programs to decarbonize bus transportation.

Meanwhile, a rising supply of low-cost renewable electricity can only be to the advantage of pilot projects for seasonal power storage, given the region’s great potential for long-term hydrogen storage. Its advantageous geography enables the presence of several geologically unique salt caverns that may be deployed for H2 storage. There are local companies already in the business of creating such salt caverns.

These pilot projects could lay the basis for an expansion phase, with more pipelines extending from the Gulf Coast to the Permian, sending CO2 and receiving low-cost natural gas. This would help foster the production of larger amounts of blue H2 for export markets. A likely candidate would be to meet growing demand in California, where public policy will require ever greater amounts of it.

And, with a major US port right there, growing demand in Europe will come into play. And locally, Houston could seek to develop new industries that need nearby hydrogen, such as a low-carbon steel industry on the Gulf Coast.

Steinhubl foresees an integrated blue-green hydrogen system, with more application of green hydrogen over time. But none of this will come cheaply. The Hydrogen Hub report recommends four key initiatives to launch blue and green H2 (see report, page 9):

· A heavy trucking pilot;

· A seasonal storage pilot using H2 caverns and low-price power;

· Connection of the existing SMR system to CCUS to create blue H2;

· Additional long-duration hydrogen storage opportunities across the Texas grid.

The report estimates that $565 million in incentives and expenditures will be required over 10 years for these pilots and initiatives.

What happens in Houston…

The DOE’s new Earthshot initiative, launched in ’21 with its first component ‘Hydrogen Shot,’ seeks to reduce the cost of clean hydrogen by 80% to $1/kg by the early 2030s.

What occurs in Houston, with its significant hydrogen-related resources, will no doubt factor importantly into this effort. Such a positive price trend will produce positive feedback, enabling the expansion of its hydrogen economy with great potential for export earnings, which in turn will open new opportunities for local economic development.

This, no doubt, is what is motivating Houston’s business and civic leaders to look seriously at low-carbon hydrogen. The pilot projects of the Hydrogen Hub report, coming into play simultaneously with the enormous CCS project of the 11-company consortium, could help transform the old oil city’s economy in a post-carbon age.

“Now we’re looking to 2050,” says Steinhubl.

Oilprice by Alan Mammoser, January 4, 2022