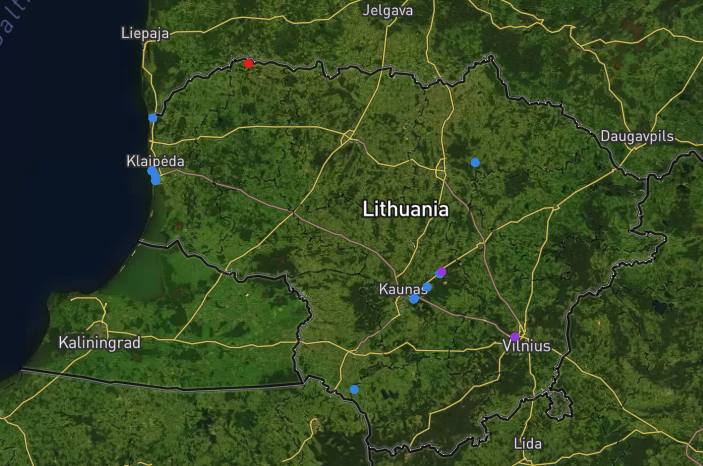

Situated in the Baltic region of Europe, the Republic of Lithuania is a developed nation with a high-income economy sustained by an advanced services sector which contributes about 68% to the country’s GDP, followed by the industrial and agriculture sectors. Also, more than 90% of all the foreign direct investment in Lithuania comes from the EU nations, with Sweden being the largest investor.

Around 18% of Lithuania’s exports comprise agro-based goods and packaged food. It is also a distinguished manufacturer of Chemical products, plastics, machinery, electronic appliances, mineral goods, wood and furniture. Its major trade partners are Russia, Latvia, Poland, Germany, Estonia, Sweden and Britain.

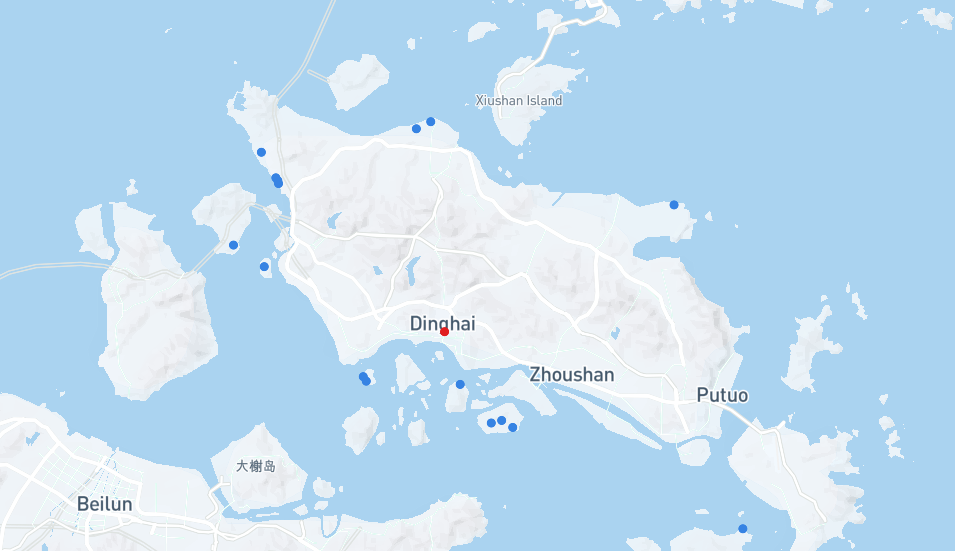

Lithuania has a 99-kilometre coastline out of which only a minuscule 38% faces the Baltic Sea while the rest is covered by the Curonian sand peninsula. Hence, Lithuania possesses only one warm-water seaport, the Klaipeda port and an oil terminal named the Butinge Marine Terminal. Let us have a look at the distinguishing features of these ports and terminals of Lithuania.

1. Port of Klaipeda

Klaipeda port is situated on the southeastern Baltic coastline where the Curonian Lagoon and the river Neman meet in Lithuania. It is 230 kilometres away from the Latvian port of Riga and around 123 nautical miles from Port Ronehamn in Sweden. Klaipeda State seaport not only engages in international maritime trade but is an important regional trade hub as well.

The only seaport of Lithuania, Klaipeda is home to 28 designated terminals and huge shipbuilding yards specialising in the construction of floating docks and fishing trawlers. It can handle more than 70 million tonnes of cargo every year and is strategically located at the crossroads of international transportation corridors connecting Europe and Asia. The multimodal facility is closest to the ports in Northern Europe and Southern Scandinavia and is known as a major container port in the Baltic region.

Klaipeda also supports the region’s profitable deep-sea fisheries sector. It has a fish cannery and other important industries engaged in the manufacture of amber jewellery, paper, cotton textiles, radio and automobile parts. Timber working is an intrinsic part of the local economy and hence wood is also a major export commodity. Diverse cargoes are handled at the port such as oil products, fertilisers, container goods, metal scrap, sugar, ferroalloys, perishable items, grain, animal fodder, peat etc.

The seaport is a valuable asset to the country as it contributes significantly to the nation’s GDP. It has also created more than 60,000 permanent jobs and has contributed to the growth of Lithuania’s industries, attracted foreign direct investment and aided in the overall development of the country.

Unlike other northern ports, Klaipeda does not freeze even during the coldest winters, enabling uninterrupted shipping and stevedoring. It is operational 24 hours a day and all days of the week making it the northernmost ice-free facility in the eastern Baltic Sea region. The universal deepwater port also houses fourteen prominent stevedoring, ship repair and construction companies offering maritime business services and efficient cargo handling.

Due to its many advantages such as the presence of a Free Economic Zone, a logistics centre and the short sea shipping network of the European Union, Klaipeda has emerged as a reliable port offering faster services to its national and international customers.

Klaipeda is also an active member of five international organisations such as the Baltic Ports Organisation, International Harbour Masters’ Association, Cruise Baltic etc through which it regularly participates in international negotiations regarding transportation issues, and also organises exhibitions and trade conferences.

The port’s increased productivity should also be attributed to the advanced port operating systems installed in its numerous terminals. For keeping a track of the general cargo and miscellaneous goods shipped through the port, a KIPIS information system has been put in place. It has increased the port’s competitive advantage and allows the companies to exchange electronic information during the cargo handling process.

The LUVIS Port Management Information System automatically manages the shipping procedures of all cargo ships, RORO ships and liquid bulk carriers including the accounting of port dues.

Port features

Klaipeda port covers around 558 hectares of land area. It has two, northern and southern breakwaters measuring 733 m and 1374 m respectively. The entrance channel is 15.5 m deep and can accommodate ships with a maximum length of 400 m, a width of 59 m and a 13.8 m draft. The total length of the port berths is 24.7 km and these can handle 200,000 DWT dry cargo vessels, about 170,000 DWT oil tankers and 20,000 TEU container ships.

Klaipeda has ample storage space such as 1,045,880 m2 of open storage area, covered general cargo yards spanning 99,380 m2 and bulk storage for keeping 933,700 tonnes. The refrigerated cargo station can keep up to 66,000 tonnes of perishable goods whereas the liquid storage tanks have a capacity for 749,000 m3 of liquid cargo.

Bulk Cargo Terminal

This facility specialises in handling mineral fertilisers and also offers bagging services. Other Bulk and general cargoes are also dealt with at its 7 multipurpose berths. With an annual cargo capacity of 16 million tonnes, the terminal’s storage complex consists of 10 covered arched warehouses with a total storage capacity of 250,000 tonnes.

It also has three wagon unloading units for receiving bulk from the railway terminal. These can unload 700 mineral carriers in 24 hours. Three ship loading machines with an aggregate capacity of 100,000 tonnes are operated by the terminal. Four ships with a draft of 14 m can be loaded simultaneously using the automated terminal system.

RORO Terminal

This modern Ro-pax terminal comprises two new berths with adjustable hydraulic ramps, a seaport complex and three terminal buildings. Different kinds of ships like Ro-ro carriers, Ro-pax, con-Ro, cruise and a few passenger vessels are accepted at this facility. Wheeled equipment can be stored in the open yard whereas more than 2500 automobiles are kept in the 10 closed warehouses.

Klaipeda Container Terminal

Three wharves at this facility can accommodate the biggest container carriers apart from dealing with some heavy cargoes. It also provides container packaging, stuffing, stripping, assembly and reloading services.

CN LNG Terminal

The port’s LNG terminal is equipped with three floating piers for receiving LNG vessels. It also provides transhipment services and transfers LNG to storage tanks from gas carriers and vice versa.

Krovinių terminalas, UAB

Numerous services such as loading and storage of petrochemical goods, oil, diesel, and fuel are offered at the Kroviniu terminal served by both railways and roadways. These goods are transported to the neighbouring nations of Belarus and Latvia.

Containing 14 storage tanks and a complex network of pipelines for transporting oil from ships to the nearby reservoir farm, it is one of the busiest facilities of Klaipeda port.

Malkų įlankos terminalas, UAB

This terminal specialises in handling agricultural goods, round and sawn timber, wooden logs, technological and fuel chips, stone, gravel, cement, peat briquettes and other bulk cargoes. It has 9 berthing facilities with a total berthing line of over 1800m2 with an alongside depth of 8.3 m.

Vakarų krova, UAB

This terminal mainly deals with shipments of fertilisers, salt, kaolin, scrap metal, limestone, biodiesel, molasses, round wood, miscellaneous packaged items as well as wheeled machinery and breakbulk. The aforementioned commodities are handled at the 4 sub-terminal facilities offering storage space for dry as well as liquid cargoes.

Western Shipyard, AB

The Klaipeda western shipyard has 5 drydocks offering ship construction, vessel conversion, repair and maintenance services. It has 4500m2 of warehouse space for keeping terminal equipment. The shipyard also manufactures metal structures and carries out metal cutting and processing. It houses 8 workshops and 5 painting shops. Scrap metal is also purchased at this facility.

Cruise Ship Terminal

Apart from being a cargo port, Klaipeda’s position near the Baltic coast’s white sand beaches and Lithuania’s most exotic coastal resort of Palanga, has transformed it into a popular tourist destination, especially crowded during summers.

The advent of cruise shipping in Klaipeda can be traced back to 2003 when the port’s Cruise ship terminal was constructed. Offering world-class facilities, the cruise terminal covers an area of 12 hectares and is just 150 m away from the Klaipeda city centre.

Ships up to 332 metres long, 45 metres wide and 8.6 metres deep can moor at the terminal’s 6 passenger berths. It is endowed with all basic amenities such as 3 waiting rooms, 5 luxurious lounges, offices of cruise ship companies, a post office, a telephone booth, free wifi, currency exchange, internet cafe, ATM, and souvenir shops, bars, restaurants and also hotels.

Central Klaipeda terminal

The central terminal was opened in 2014 and is capable of serving around 500,000 passengers every year. It houses a huge logistics area and a 14-hectare open cargo storage site capable of storing about 600 trailers. It also has a 4000m2 warehouse space and a modern terminal management system that was installed in 2017.

It also comprises three terminal buildings, cafes, a ticketing office and numerous wheelchair ramps and signboards since it is adapted for people with disabilities. In 2018, it was equipped with electric vehicle charging stations. It can also handle non-standard heavy cargo and has 8 parking lots. Business clients can use the conference room located in the main terminal building.

The eastern part of the facility is used as a ferry terminal where small ships sail to nearby regions and countries like Latvia, Sweden and Germany.

2. Butinge Marine Terminal

Butinge Terminal is an oil facility located near the Butinge village in the Palanga municipality on the northern Baltic sea coast, close to the border of Latvia. It was planned, designed and constructed by the Fluor Corporation and is a part of Orlen Lietuva, a subsidiary of the PKN Orlen Group based in Poland and the owner of the Mazeikiai oil refinery of Lithuania, the only oil refinery of the Baltic region.

Situated near the mouth of the Sventoji river and spanning 1239 hectares, this was the first large scale petroleum project undertaken by the country after attaining its independence in 1990.

The single-point mooring terminal can offload up to 4932 m3 per hour. Apart from the floating buoy; an oil pipeline, numerous pumping stations, a wastewater treatment plant and an offshore facility are a part of the Butinge Marine terminal, capable of handling 8 million tonnes of crude oil meant for exportation and around 6 tonnes of oil for import.

The crude oil single-point mooring facility can accommodate tankers weighing up to 80,000 DWT. It is linked to the shore through an offshore underwater pipeline measuring 3 feet in diameter and covering 7.5 kilometres.

The onshore terminal’s storage facilities comprise three 50,000 m3 floating roof tanks for keeping crude oil and four fixed roof tanks dedicated to diesel fuel and slop oil. It is also equipped with a powerful pumping system for loading and unloading oil tankers.

A 22-inch crude oil pipeline is used for transporting the products between the Butinge marine terminal and the Mazeikiai Refinery situated 56 miles from the facility.

marineinsight, by Shilavadra Bhattacharjee April 19, 2022