South Korea finds competitive US crude highly attractive in times of surging benchmark oil prices, but Asia’s biggest US crude customer also aims to enhance its green energy practices by gradually increasing the share of net-zero crude oil in the overall feedstock imports from the North American producer.

Major South Korean refiners said light sweet US crude grades are typically placed on the list of top monthly feedstock choices, especially in times of high global energy prices, as the North American barrels come cheaper than many Middle Eastern grades thanks to US-South Korea free trade agreement. Persian Gulf producers, on the other hand, continue to raise their official selling prices.

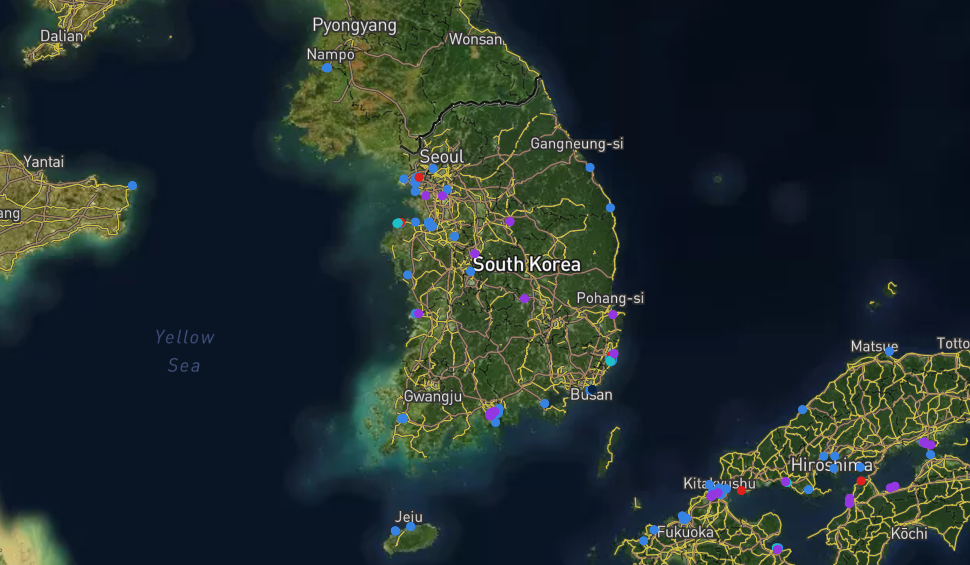

South Korean refiners paid on average $78.88/b for shipments of US grades in January, lower than $82.98/b paid for Saudi Arabian crude imports and more than $7/b cheaper than $85.94/b paid for Kuwaiti barrels, according to the latest data from state-run Korea National Oil Corp. The world’s fourth biggest crude importer took 119 million barrels of crude oil from the US in 2021.

Apart from feedstock economics, crude oil trading managers and officials at major South Korean refiners told S&P Global Commodity Insights that the companies have not forgotten about their commitments to reduce their carbon footprint and they are closely monitoring the growing availability of low carbon crude in the US and Europe.

The country’s top refiner SK Innovation said March 25 it plans to purchase 200,000 barrels/year of “net zero” crude oil from Occidental Petroleum Corp. for five years from 2025.

The company’s trading arm SK Trading International has signed the deal with the Permian-based producer in an effort to accelerate the company’s energy transition initiative, an official at SK Innovation said.

SK Innovation said it will refine the crude oil from Occidental into “net zero oil products” such as eco-friendly jet fuel so as to help reduce carbon emissions and combat climate changes.

“Buying US crude, it’s not all about just cutting costs or saving dollars and cents … US crude producers are rapidly enhancing their carbon capture technology and it’s sensible for an end-user with right ESG mindset to fully support and appreciate such efforts,” a feedstock and plant operation manager at SK Innovation’s Ulsan refinery said.

Net-zero oil, CCUS technology

Net zero oil refers to barrels produced through the direct capture and sequestration of atmospheric carbon dioxide via industrial-scale direct air capture facilities and geological sequestration, unlike those “carbon neutral crude” claimed by upstream companies by simply offsetting emissions using carbon credits, the SK Innovation official said.

SKTI explained that Occidental’s first net-zero oil is created by blending crude oil with environmental attributes generated from the sequestration of atmospheric carbon dioxide captured via 1PointFive’s multi-solution platform for Carbon Capture, Utilization and Sequestration, or CCUS.

According to Occidental, 1PointFive is a CCUS platform with a singular purpose to help curb global temperature rise to 1.5°C by 2050 through the commercialization of decarbonization solutions including Carbon Engineering’s Direct Air Capture, or DAC, Air To Fuels technologies and geologic sequestration.

1PointFive’s first DAC facility, which is expected to be online late 2024, will also include pure sequestration and is in the process of being deployed using Carbon Engineering’s industrial-scale DAC solution. The facility will extract atmospheric CO2 and permanently store it deep underground in geologic formations delivering permanent and verifiable carbon dioxide removal, according to SKTI.

“We are pleased to be a part of the world’s first carbon emission reduction initiative that is underpinned by processing net-zero oil on a life-cycle analysis basis. We are also thrilled to team up with Occidental, one of the most respected energy companies in the world,” Sokwon Suh, CEO of SKTI, said.

Carbon-neutral European crude

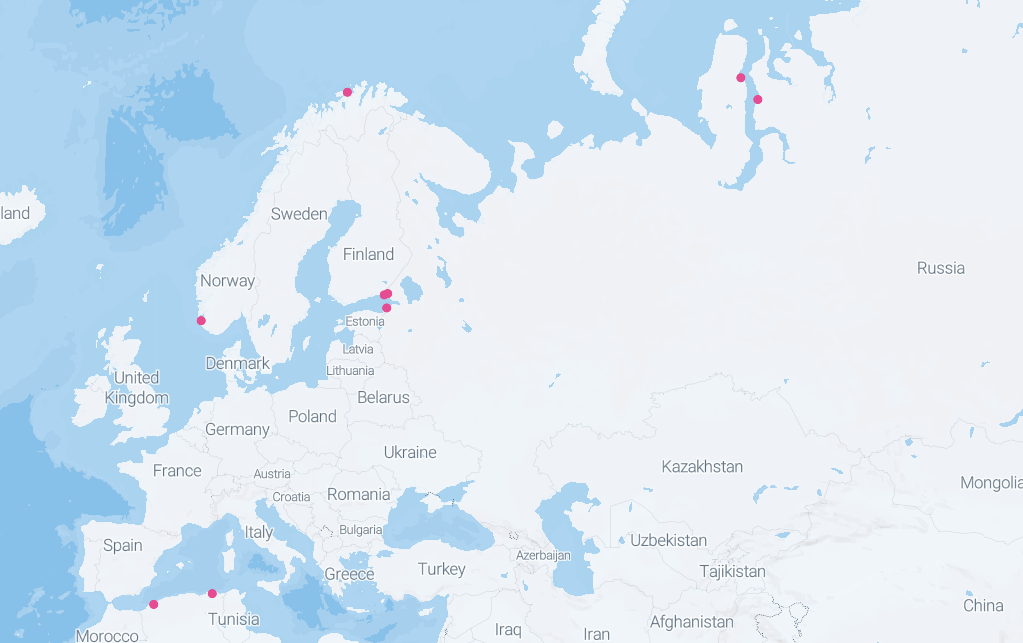

The latest agreement with SKTI and Occidental indicated that South Korean refiners are actively looking for ways to enhance and incorporate their ESG considerations from the feedstock front, with the country also expected to continue embracing carbon-neutral crude from Norway, according to market research analysts at Korea Petroleum Association.

South Korea’s second-largest refiner GS Caltex had purchased 2 million barrels of Norway’s Johan Sverdrup crude certified as carbon neutral at the point of production for delivery in September 2021.

GS Caltex has been buying Johan Sverdrup crude on a regular basis since then, with South Korea importing more than 17 million barrels of crude from Norway in 2021, compared with 8.5 million barrels received in 2020, 1 million barrels in 2019 and 5 million barrels in 2018, according to the latest data from state-run Korea National Oil Corp.

In June 2021, Sweden’s Lundin Energy, a partner in Norway’s giant Johan Sverdrup oil field, said all future net production from Johan Sverdrup will be certified as carbon neutral produced by Intertek, under its CarbonZero standard.

S&P Global by Gawoon Philip Vahn, March 31, 2022