We are halfway through the first month of the new year, and oil’s bull run is showing no signs of slowing. Oil futures have vaulted 12% in the first two trading weeks of the new year, boosted by several catalysts, including supply constraints, worries of a Russian attack on neighboring Ukraine, and growing signs the Omicron variant won’t be as disruptive as feared.

Brent crude futures settled $1.59, or 1.9%, higher in Friday’s session at a 2-1/2-month high of $86.06 a barrel, gaining 5.4% in the week, while U.S. West Texas Intermediate crude gained $1.70, or 2.1%, to $83.82 per barrel, rising 6.3% in the week. Both Brent and WTI futures have now entered overbought territory for the first time since late October.

“People looking at the big picture realize that the global supply versus demand situation is very tight and that’s giving the market a solid boost,” Phil Flynn, senior analyst at Price Futures Group, has told Reuters.

“When you consider that OPEC+ is still nowhere near pumping to its overall quota, this narrowing cushion could turn out to be the most bullish factor for oil prices over the coming months,” PVM analyst Stephen Brennock has said.

Indeed, several banks have forecast oil prices of $100 a barrel this year, with demand expected to outstrip supply, thanks in large part to OPEC’s limited capacity.

Morgan Stanley predicts that Brent crude will hit $90 a barrel in the third quarter of this year, while JPMorgan has forecast oil to hit $125 a barrel this year and $150 in 2023. Meanwhile, Rystad Energy’s senior vice-president of analysis, Claudio Galimberti, says if OPEC was disciplined and wanted to keep the market tight, it could boost prices to $100.

OPEC+ has lately come under pressure to ramp up production at a faster clip from several quarters, including the Biden administration so as to ease supply shortages and rein in spiraling oil prices. But the organization is scared of spoiling the oil price party by making any sudden or big moves with last year’s oil price collapse still fresh on its mind.

But maybe we have been overestimating how much power the cartel has to jack up production on the fly.

According to a recent report, at the moment, just a handful of OPEC members are capable of meeting higher production quotas compared to their current clips.

Amrita Sen of Energy Aspects has told Reuters that only Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Iraq, and Azerbaijan are in a position to boost their production to meet set OPEC quotas, while the other eight members are likely to struggle due to sharp declines in production and years of underinvestment.

Underinvestments stalling recovery

According to the report, Africa’s oil giants Nigeria and Angola are the hardest hit, with the pair having pumped an average of 276kbpd below their quotas for more than a year now.

The two nations have a combined OPEC quota of 2.83 million bpd according to Refinitiv data, but Nigeria has failed to meet its quota since July last year and Angola since September 2020.

In Nigeria, five onshore export terminals run by oil majors with an average production clip of 900,000 bpd handled 20% less oil in July than the same time last year despite relaxed quotas. The declines are due to lower production from all the onshore fields that feed the five terminals.

In fact, only French oil major TotalEnergies‘(NYSE:TTE) new deep offshore oilfield and export terminal Egina has been able to quickly ramp up production. Turning the taps back on has been proving to be a bigger challenge than earlier thought due to a shortage of workers, huge maintenance backlogs, and tight cash flows.

Indeed, it could take at least two quarters before most companies can work through their maintenance backlogs which cover everything from servicing wells to replacing valves, pumps, and pipeline sections. Many companies have also fallen behind on plans to do supplementary drilling to keep production stable.

Angola has not been faring any better.

In June, Angola’s oil minister, Diamantino Azevedo, lowered its targeted oil output for 2021 to 1.19 million bpd, citing production declines at mature fields, drilling delays due to COVID-19 and “technical and financial challenges” in deepwater oil exploration. That’s nearly 11% below its 1.33 million bpd OPEC quota and a far cry from its record peak above 1.8 million bpd in 2008.

The southern African nation has struggled for years as its oil fields steadily declined while exploration and drilling budgets failed to keep up. Angola’s largest fields began production about two decades ago, and many are now past their peaks. Two years ago, the country adopted a string of reforms aimed at boosting exploration, including allowing companies to produce from marginal fields adjacent to those they already operate. Unfortunately, the pandemic has stunted the impact of those reforms, and not a single drilling rig was operational in the country by May, the first time this has happened in 40 years.

So far, just three offshore rigs have resumed work.

Shale decline

But it’s not just OPEC producers that are struggling to boost oil production.

In an excellent op/ed, vice chairman of IHS Markit Dan Yergin observes that it’s almost inevitable that shale output will go in reverse and decline thanks to drastic cutbacks in investment and only later recover at a slow pace. Shale oil wells decline at an exceptionally fast clip and therefore require constant drilling to replenish lost supply.

Indeed, Norway-based energy consultancy Rystad Energy recently warned that Big Oil could see its proven reserves run out in less than 15 years, thanks to produced volumes not being fully replaced with new discoveries.

According to Rystad, proven oil and gas reserves by the so-called Big Oil companies, namely ExxonMobil, BP Plc. (NYSE:BP), Shell (NYSE:RDS.A), Chevron (NYSE:CVX), TotalEnergies SE (NYSE:TTE), and Eni S.p.A (NYSE:E) are all falling, as produced volumes are not being fully replaced with new discoveries.

Granted, this is more of a long-term problem whose effects might not be felt soon. However, with the rising sentiment against oil and gas investments, it’s going to be hard to change this trend.

Experts are warning that the fossil fuel sector could remain depressed thanks to a big nemesis: the trillion-dollar ESG megatrend. There’s growing evidence that companies with low ESG scores are paying the price and are increasingly being shunned by the investing community.

According to Morningstar research, ESG investments hit a record $1.65 trillion in 2020, with the world’s largest fund manager, BlackRock Inc. (NYSE:BLK), with $9 trillion in assets under management (AUM), throwing its weight behind ESG and oil and gas divestitures.

Michael Shaoul, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of Marketfield Asset Management, has told Bloomberg TV that ESG is largely responsible for lagging oil and gas investments:

“Energy equities are nowhere close to where they were in 2014 when crude oil prices were at current levels. There are a couple very good reasons for that. One is it’s been a terrible place to be for a decade. And the other reason is the ESG pressures that a lot of institutional managers are on lead them to want to underplay investment in a lot of these areas.”

In fact, U.S. shale companies are now facing a real dilemma after disavowing new drilling and prioritizing dividends and debt paydowns, yet their inventories of productive wells continue falling off a cliff.

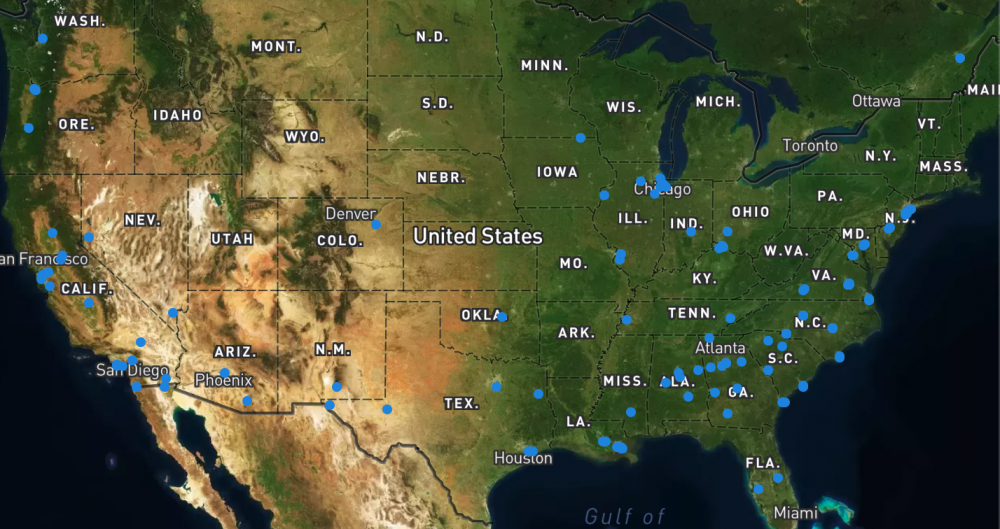

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, the United States had 5,957 drilled but uncompleted wells (DUCs) in July 2021, the lowest for any month since November 2017 from nearly 8,900 at its 2019 peak. At this rate, shale producers will have to sharply ramp up the drilling of new wells just to maintain the current production clip.

If we need any more proof that shale drillers are sticking to their newfound psychology of discipline, there is recent data from the EIA. That data shows a sharp decline in DUCs in most major U.S. onshore oil-producing regions. This, in turn, points to more well completions but less new well drilling activity. It’s true that higher completion rates have been leading to an uptick in oil production, particularly in the Permian; however, those completions have sharply lowered DUC inventories, which could limit oil production growth in the United States in the coming months.

That also means that spending will have to increase if we are to see shale keep pace with production declines. More will have to come online, and that means more money.