Country is hoping a new North Sea terminal can supply 8% of its gas usage as war in Ukraine upends energy policy.

As tourists at the Hooksiel resort on Germany’s North Sea coastline lean back in their wicker beach chairs or stomp around the mud flats, the cast-iron jetty that stretches for 1.3km into the ocean to their right is a familiar sight. The frantic clanging of metal on metal at its furthest tip, however, is new.

Built in 1982, the jetty was designed to host not just two import terminals for chemicals but also one for liquefied natural gas (LNG), shipped in on tankers from the US. With cheap Russian gas beating LNG for price, those tankers never arrived. Two adjacent plots of land, reclaimed from the North Sea to make space for industry, instead attracted rare warblers and bitterns.

But as Russia’s war in Ukraine upends decades of German energy policy, getting LNG tankers to dock on the Hooksiel jetty is suddenly a matter of national priority.

Wilhelmshaven, the nearby historic port city, has become emblematic of a two-fold, seemingly contradictory promise made by Germany’s government: that it can import LNG to compensate for throttled gas imports from Russia at record speed, belying a reputation for bureaucratic plodding; and that the jetty into the North Sea will carry LNG – a polluting fossil fuel – for only a short time, soon to be replaced with a more climate-friendly substitute.

Wilhelmshaven is one of five floating LNG terminals Germany is rushing to build by the end of the year, creating infrastructure that a study in July by the Fraunhofer Institute argued would be vital to avoid cold homes and closed factories this winter not just in Germany but across all of Europe as Vladimir Putin turns off the tap.

The Höegh Esperanza, a 300-metre long tanker converted into a Floating Storage and Regasification Unit and chartered by the German government at a mooted cost of €200,000 a day, will dock at the jetty and turn liquid back into gas at a rate of about 10 hours per tanker load.

Roughly 80 tankers are expected to arrive at Wilhelmshaven each year, substituting half of the gas imports the German energy company Uniper used to have from Russia, or 8% of Germany’s overall gas usage before the start of the war.

Shortly after Russian troops crossed on to Ukrainian soil in the spring, the talk was that building LNG terminals would take three to five years. Now politicians are confident the terminal and its connecting pipeline can be built in seven months, with works finishing on 21 December and gas flowing the day after.

Uniper, which is managing the build, is only slightly more cautious, saying windy weather in the colder months could yet delay completion until the second half of the winter.

Behind-schedule building projects, such as Berlin’s new airport and Hamburg’s Elbphilharmonie concert hall, have in recent years busted myths of German efficiency. The LNG terminals are trying to buck the trend by instead emulating the model behind the creation of Tesla’s new Gigafactory in Brandenburg, with building works already starting while permit applications are still being scrutinised.

“Everything that’s usually done step by step, we are now doing in parallel,” said Holger Kreetz, Uniper’s chief operating officer for asset management, on a boat trip to the far end of the Hooksiel jetty at the start of the week.

Environmental impact assessments, usually a requisite step, are simply being skipped. The economic affairs minister, Robert Habeck, a Green party politician and self-proclaimed “biggest porpoise fan in the government”, has shrugged off concerns that building works could disturb the endangered aquatic mammals basking in Jade Bay. Ensuring Germany was no longer blackmailable by Putin had to take priority, he said.

Germany’s about-face from Russian natural gas pipelines to shipped-in LNG will not just test the political credibility of the Greens. “It’s hard to admit, but we probably wouldn’t have got around to building these terminals so quickly if it wasn’t for the war,” said Olaf Lies, the centre-left Social Democrat environment minister for the state of Lower Saxony. “To an extent, what is happening in Wilhelmshaven now also shows up the political failures of the past. We got too comfortable and neglected other projects we should have tackled.”

The hope is that Europe’s energy crisis could be an opportunity to take strides towards a greener future rather than be a setback for its climate targets, said Lies, who insisted that the Hooksiel jetty would host a “molecule terminal” rather than one specific to LNG.

As Germany has committed to being greenhouse gas-neutral by 2045, the pipelines on the North Sea coast would soon not be pumping LNG but green hydrogen, produced by using renewable electricity to drive an electrolyser that splits water into hydrogen and oxygen, Lies said in an interview.

Some of the green hydrogen would be produced in Wilhelmshaven, where Uniper is converting a phased-out coal plant into an electrolyser. The rest would be imported via the new terminal infrastructure.

Open Grid Europe, the company connecting the terminal to the national gas grid, said its pipelines were 100% hydrogen-compatible barring some additional insulation before a switch over. Tests are proceeding to establish whether a natural underground salt dome outside Wilhelmshaven, where German emergency crude oil supplies have been stored since the 1970s, could hold hydrogen.

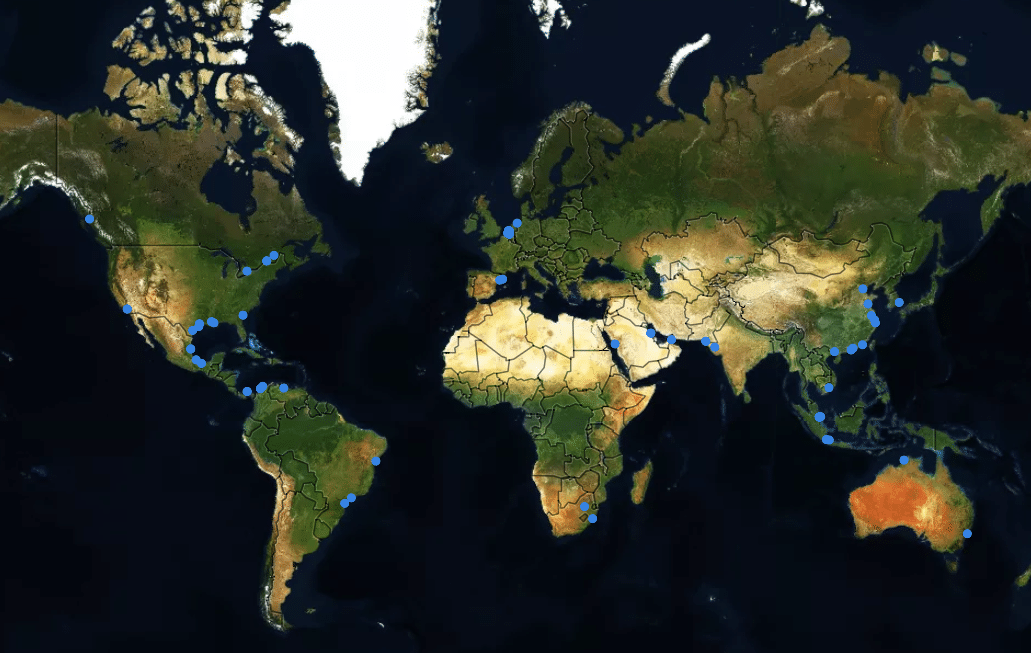

“The big energy exporters of tomorrow aren’t going to be those countries rich in natural gas, but the ones that have plenty of wind, sun and water,” Lies said, painting a picture of his home town’s reinvention as a renewable energy hub for imports from Australia, South America and Africa. “Green Wilhelmshaven” brochures have already been printed.

Among Wilhelmshaven’s residents some scepticism remains. The coastal city north of Bremen is a place of superlatives: the largest hub for Germany’s military, which coordinates its maritime forces from here; the country’s only German deepwater port; and the largest import terminal for crude oil, pumped all the way down into the industrial heartland in the Rhine valley. It was here that a sailors’ revolt against the Kaiser’s orders in October 1918 set off a chain of events that swept away the old German empire.

But triumphant highs in Wilhelmshaven’s history have been swiftly followed usually by humiliating lows. After emerging as a pirate stronghold in the 14th century its fortress was destroyed by the Hanseatic League. Flourishing as the hub of the German imperial navy under the rule of Kaiser Wilhelm II, it was cut down to size by the restrictions of the Versailles Treaty. After Hitler used the square in front of Wilhelmshaven to denounce the naval agreement with Britain, in April 1939 came Allied bombs, destroying two-thirds of the city’s residential buildings.

The city’s unemployment rates have still not recovered from the closure of the typewriter maker Olympia in 1991 and a loss of almost 3,000 jobs.

Floating LNG terminals are unlikely to change that, since they come with their own trained staff; one official put the number of jobs created at no more than 20.

While the new terminal will not spoil the vista from Wilhelmshaven’s Südstrand tourist spot, or stink out the seaside air, some residents have concerns around the project’s long-term function.

“It’s an opportunity, but also a risk,” said Fritz Santjer, an electrical engineer and member of Scientists for Future, an initiative started three years ago in support of the Fridays for Future climate movement.

Santjer, who lives on a green plot of land by the dyke in the neighbouring village of Sande, added: “If the government follows up on its plans to expand offshore wind farms, then we’re making real progress to meet the Paris agreement, and floating LNG terminals could be a good bridging technology on that path. But what if we have a new government in four years, which decides the targets are unrealistic and is quite happy to keep pumping fracking gas? Are we certain Germany will switch to hydrogen then? Do we know whether it will be green or blue?”

The pressure group Environmental Action Germany warns that the pipelines built in Wilhelmshaven will create more capacity for gas imports than required to bridge a nervous winter, and also lead Germany to miss its carbon reduction targets.

Last Friday, climate activists blocked parts of the pipeline building site at Hooksiel and poured sand into the tanks of diggers. A spokesperson said the damage caused would not set back the works’ timeline.

While the enthusiasm of German politicians and energy companies for green hydrogen is palpable, economic realities may yet tie them to non-renewable gas for longer than they desire. China and Japan, the globe’s largest importers of LNG, have underused their long-term options with suppliers this summer, allowing Europe to rake in their off-takes. Come winter, they may insist on their share of the market, forcing countries like Germany into long-term commitments.

Berlin’s negotiations over an LNG deal with Qatar are reportedly proving more difficult than expected, because the gas-rich Middle Eastern state was insisting on a contract running over 20 years until 2042.

For Wilhelmshaven to become the symbol of Germany’s carbon neutrality success in 2045, the country needs to keep up its newly found momentum.

By The Guardian, August 19, 2022